Even though major media headlines have proclaimed 2018 as “the year of the woman” thanks to an unprecedented number of female candidates entering politics, real-world numbers paint a decidedly less rosy picture for gender equality overall.

For example, in 2018, women made up less than one-quarter of the U.S. Congress, women held merely 5 percent of CEO positions at companies on the S&P 500, and women earned, on average, 82 cents to the dollar compared to their male colleagues.

Similarly, the average proportion of female faculty members at the 15 top-ranked electrical and computer engineering programs in the United States is roughly 13 percent.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison exceeds that total, with eight out of 43—or about 19 percent—of electrical and computer engineering faculty members who are women.

That’s a number that speaks to the importance the UW-Madison College of Engineering places on increasing diversity and fostering a welcoming, inclusive climate.

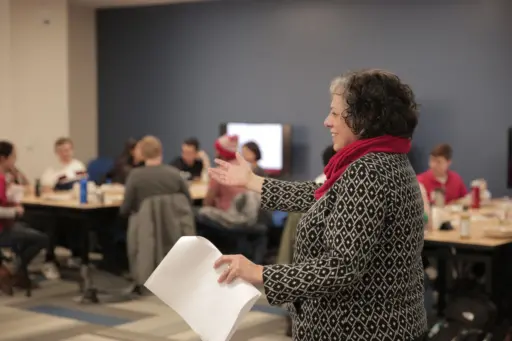

Manuela Romero leads a group discussion about implicit biases during a Breaking the Bias Habit workshop.

Manuela Romero leads a group discussion about implicit biases during a Breaking the Bias Habit workshop.

“Recognizing our biases is about our values, and how these values call us to be as leaders,” says college Associate Dean for Undergraduate Affairs Manuela Romero.

In one aspect of ongoing initiatives to enhance climate on the engineering campus, Romero collaborates with researchers in the college’s Women in Science and Engineering Leadership Institute (WISELI).

WISELI researchers have developed several nationally and internationally recognized programs and workshops on topics that include diversity and climate. Among those is one called Breaking the Bias Habit; it focuses on a specific type of bias called implicit bias.

Understanding implicit bias

Most people recognize overtly racist or sexist behavior and consciously avoid it. But other—often more subtle—behaviors can turn a workplace, research laboratory or classroom into a hostile environment.

Maybe a professor calls on male students much more often than the women in the class. Perhaps a teaching assistant schedules a review session that conflicts with a religious holiday and doesn’t offer alternative arrangements. Even seemingly innocuous statements intended as compliments—“he’s so articulate for a foreign student,” or “she’s better at math than I expected”—perpetuate harmful assumptions.

“People have stereotypes. All of us do,” says Romero. “People act without thinking.”

Yet acting without thinking has consequences. Small slights, known as microaggressions, can take a big toll, making people feel attacked, isolated and unwelcome.

Unconscious biases also can lead to unfair hiring practices. For example, research shows that people rank job applications from candidates with female names as less qualified than identical resumes with male names. Similarly, resumes with non-white-sounding names are less likely to receive callbacks for job interviews.

Even in the classroom, teachers give male students higher grades on science and math tests when they are aware of their students’ genders—yet women outperform men when grading is gender-blind.

The tricky thing about implicit biases is that most people don’t consciously engage in them—and therefore they aren’t aware that they need to change their behavior. “People think ‘I’m not actively harassing people, so I don’t have bias,’” says Jennifer Sheridan, WISELI executive and research director.

That’s why awareness is the first step toward breaking the bias habit.

Learning from a coffee catastrophe

Participants in a Breaking the Bias Habit workshop talk about their own experiences and devise plans to create a more welcoming environment.

Participants in a Breaking the Bias Habit workshop talk about their own experiences and devise plans to create a more welcoming environment.

On May 29, 2018, Starbucks shut down more than 8,000 stores so that employees could receive implicit bias training. Many people questioned whether an afternoon-long workshop could truly be enough to unravel deeply held unconscious prejudices, but there is evidence that short interventions can go a long way.

In fact, UW-Madison has been a testing ground for implicit bias training for years. In 2010, WISELI implemented a first-of-its-kind randomized, controlled study of an implicit bias workshop for faculty. The massive study, which focused on gender equality, encompassed 92 departments (or department-like units) at UW-Madison; 46 departments received the bias training, while the other 46 did not.

What happened during the workshops? Facilitators reviewed research on the pervasiveness of gender bias in STEM fields, and made the case that science must draw upon all the nation’s talent—regardless of gender—in order to advance. Participants learned proven strategies to avoid unconscious biases and reflected on how achieving gender equity might benefit their own field of study.

The outcome: Compared with faculty in the untrained control group, faculty who received implicit bias training reported significantly higher awareness of implicit bias and intention to prevent gender bias from emerging. What’s more, three years after the training, workshop attendees increased the proportion of new female faculty by roughly 18 percent, whereas hiring rates for women remained flat in the control departments.

Encouraged by the initial study’s success, the College of Engineering partnered with WISELI to offer implicit bias training to all faculty, staff and students in the College, as well as members of hiring committees.

An important—and giant—next step

Addressing implicit bias for faculty and staff members of hiring committees and at faculty meetings is one step toward improving campus climate; UW-Madison has approximately 2,100 faculty, while its student enrollment is nearly 44,000.

Students face their own unique challenges—which is why WISELI adapted its implicit bias workshop for undergraduates. Initially, the College of Engineering rolled out the training to student organization leaders. But it doesn’t stop there.

“We have a vision to reach everyone in the college. At some point this will be in an introductory course,” says Romero.

Additionally, WISELI is working with the UW-Madison Materials Research Science & Engineering Center (MRSEC) to implement implicit bias training for graduate students.

“Graduate students can be agents of change throughout their career, so it’s important to reach them now,” says MRSEC interdisciplinary education group co-director Wendy Crone, who is a professor of nuclear engineering and engineering physics. “Our graduate students are some of the very best in the country. When they are hired in faculty positions elsewhere or go into industry, we hope they can take not only the training but also the attitude and awareness that inclusion matters.”

Those attitudes have benefits far beyond making the STEM fields more welcoming for women and people in minority groups. Several funding agencies, including the National Science Foundation, have for years required researchers to describe how their projects will promote diversity and inclusion on grant applications.

And that reflects an appreciation that engineering education must include much more than formulas and equations: Tomorrow’s leaders must also be able to communicate, empathize, respect, and work in diverse teams. And they’re learning to do just that in the UW-Madison College of Engineering.