If Ashley Hiebing is being honest, the questions and insecurities still rattle around her head.

Am I good enough?

Am I smart enough?

Am I anything enough to be doing what I’m doing?

Hiebing, a PhD student in biomedical engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is far from alone in grappling with imposter syndrome, especially among women in science, technology, engineering and math fields.

Not only is Hiebing a first-generation college student from a working class family in the small northern Madison suburb of DeForest—she’s also rebounded after two scrapped attempts at college and worked her way up from Algebra 1 to conducting computational modeling of cardiovascular growth over the past eight years.

“I think even now I’m still trying to prove to myself that I can do this,” she says.

And yet there is ample external proof that Hiebing can indeed succeed as a scientist, including her having earned a prestigious National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to support her doctoral studies. By Hiebing’s own admission, it was an improbable achievement for someone who felt aimless after high school and worked a string of minimum-wage jobs between brief stints at Herzing University and Madison College.

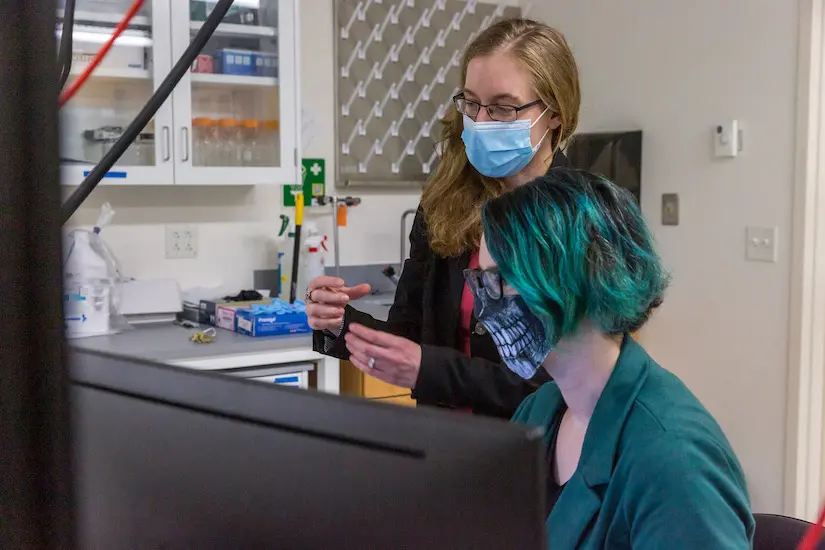

Ashley Hiebing and Assistant Professor Colleen Witzenburg work in their lab in the Engineering Centers Building.

Ashley Hiebing and Assistant Professor Colleen Witzenburg work in their lab in the Engineering Centers Building.

“I wasn’t ready for it. I wasn’t mature enough to handle the college courseload,” says Hiebing, who at age 23 decided to give college a third try.

She set her sights on biomedical engineering, a field that would allow her to help people from behind the scenes while proving to herself that she could conquer a totally unfamiliar challenge.

First, though, she needed to complete a whole host of basic prerequisites, so she returned to Madison College in 2013 and rebuilt her math skills over three years before transferring to Milwaukee School of Engineering (MSOE). She earned membership in two engineering honor societies at MSOE, completed an undergraduate research experience at the University of Minnesota, and made the dean’s list all six years across both schools.

“I felt like I knew where I wanted to go and I knew what I needed to do to get there,” says Hiebing.

She originally envisioned that destination being the neural tissue engineering field, until a MATLAB programming course at MSOE hooked her. She pivoted from modeling neurological processes after hitting it off with UW-Madison Assistant Professor Colleen Witzenburg, who uses a combination of mechanical experimentation and computational modeling to study cardiovascular tissue structure and function, while surveying graduate school possibilities at the Biomedical Engineering Society annual meeting in 2018.

“When Ashley indicated me as a potential advisor, I was surprised since her research experience was in neurobiology. After talking more, though, it became clear that her passion was computer modeling and that she would be a strong graduate student,” says Witzenburg, who is applying her work to a condition called hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), in which children are born with one side of the heart crucially underdeveloped. “Biomechanics is a math-heavy discipline. So Ashley’s tenacity at learning tough new content and ease in applying her coding experience to a new area is incredibly impressive.”

Hiebing has poured herself into studying up on HLHS, setting up Google Scholar alerts for terms like “single ventricle” and reading about treatment plans and surgical techniques. She even got an anatomically correct heart tattooed on her left arm.

Children born with HLHS require a series of three surgeries before age 3, rerouting the blood flow from their hearts to buy them time for a heart transplant. But the timing of the second surgery in particular is crucial to safeguarding the overtaxed right ventricle.

In Witzenburg’s lab, Hiebing is helping to build a modeling tool that would allow clinicians to predict the dimensions of a patient’s heart, enabling them to more precisely plan the timing of the surgeries for each child. Right now, lab members have created a reliable model for cardiovascular growth in a healthy infant, from which they’ll build out a simulation tailored to patients with HLHS.

“I love making computational models,” says Hiebing. “I think being able to break a complex process down into a computer simulation, into binary values, zeroes and ones, that’s amazing to me. It’s like painting the Sistine Chapel with crayons, but I enjoy the challenge.”

Hiebing is still formulating her plan beyond grad school; she’s currently leaning toward a career in industry. For now, however, she’s focused on helping kids with HLHS. And she’s grateful that her roundabout journey has led her to fulfilling work.

“I have zero regrets,” she says. “I feel like I am where I need to be, and every step that I’ve taken to get here were the steps that I needed to take when I took them.”